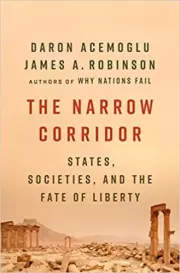

Daron Acemoglu - The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty

| Название: | The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty |

Автор: | Daron Acemoglu | |

Жанр: | Старинная литература | |

Изадано в серии: | неизвестно | |

Издательство: | неизвестно | |

Год издания: | 2019 | |

ISBN: | неизвестно | |

Отзывы: | Комментировать | |

Рейтинг: | ||

Поделись книгой с друзьями! Помощь сайту: донат на оплату сервера | ||

Краткое содержание книги "The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty"

From the authors of the international bestseller Why Nations Fail, a crucial new big-picture framework that answers the question of how liberty flourishes in some states but falls to authoritarianism or anarchy in others--and explains how it can continue to thrive despite new threats. In Why Nations Fail, Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson argued that countries rise and fall based not on culture, geography, or chance, but on the power of their institutions. In their new book, they build a new theory about liberty and how to achieve it, drawing a wealth of evidence from both current affairs and disparate threads of world history. Liberty is hardly the "natural" order of things. In most places and at most times, the strong have dominated the weak and human freedom has been quashed by force or by customs and norms. Either states have been too weak to protect individuals from these threats, or states have been too strong for people to protect themselves from despotism. Liberty emerges only when a delicate and precarious balance is struck between state and society. There is a Western myth that political liberty is a durable construct, arrived at by a process of "enlightenment." This static view is a fantasy, the authors argue. In reality, the corridor to liberty is narrow and stays open only via a fundamental and incessant struggle between state and society: The authors look to the American Civil Rights Movement, Europe’s early and recent history, the Zapotec civilization circa 500 BCE, and Lagos’s efforts to uproot corruption and institute government accountability to illustrate what it takes to get and stay in the corridor. But they also examine Chinese imperial history, colonialism in the Pacific, India’s caste system, Saudi Arabia’s suffocating cage of norms, and the “Paper Leviathan” of many Latin American and African nations to show how countries can drift away from it, and explain the feedback loops that make liberty harder to achieve. Today we are in the midst of a time of wrenching destabilization. We need liberty more than ever, and yet the corridor to liberty is becoming narrower and more treacherous. The danger on the horizon is not "just" the loss of our political freedom, however grim that is in itself; it is also the disintegration of the prosperity and safety that critically depend on liberty. The opposite of the corridor of liberty is the road to ruin.

Читаем онлайн "The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty". [Страница - 5]

subject to arbitrary sway: being subject to the potentially capricious will or the potentially idiosyncratic judgement of another.

We refine Locke’s notion and define liberty as the absence of dominance, because one who is dominated cannot make free choices. Liberty, or in Pettit’s words, non-dominance, means

emancipation from any such subordination, liberation from any such dependency. It requires the capacity to stand eye to eye with your fellow citizens, in a shared awareness that none of you has a power of arbitrary interference over another.

Critically, liberty requires not just the abstract notion that you are free to choose your actions, but also the ability to exercise that freedom. This ability is absent when a person, group, or organization has the power to coerce you, threaten you, or use the weight of social relations to subjugate you. It cannot be present when conflicts are resolved by actual force or its threat. But equally, it doesn’t exist when conflicts are resolved by unequal power relations imposed by entrenched customs. To flourish, liberty needs the end of dominance, whatever its source.

In Lagos liberty was nowhere to be seen. Conflict was resolved in favor of the stronger, the better-armed party. There was violence, theft, and murder. Infrastructure was crumbling at every turn. Dominance was all around. This was not a coming anarchy. It was already there.

Warre and the Leviathan

Lagos in the 1990s may seem an aberration to most of us living in security and comfort. But it isn’t. For most of human existence, insecurity and dominance have been facts of life. For most of history, even after the emergence of agriculture and settled life about ten thousand years ago, humans lived in “stateless” societies. Some of these societies resemble a few surviving hunter-gatherer groups in the remote regions of the Amazon and Africa (sometimes also called “small-scale societies”). But others, such as the Pashtuns, an ethnic group of about 50 million people who occupy much of southern and eastern Afghanistan and northwestern Pakistan, are far larger and engaged in farming and herding. Archaeological and anthropological evidence shows that many of these societies were locked in an even more traumatic existence than the inhabitants of Lagos suffered daily in the 1990s.

The most telling historical evidence comes from deaths in warfare and murder, which archaeologists have estimated from disfigured or damaged skeletal remains; some anthropologists have observed this firsthand in surviving stateless societies. In 1978, the anthropologist Carol Ember systematically documented that there were very high rates of warfare in hunter-gatherer societies—a shock to her profession’s image of “peaceful savages.” She found frequent warfare, with a war at least every other year in two-thirds of the societies she studied. Only 10 percent of them had no warfare. Steven Pinker, building on research by Lawrence Keeley, compiled evidence from twenty-seven stateless societies studied by anthropologists over the past two hundred years, and estimated a rate of death caused by violence of over 500 per 100,000 people—over 100 times the current homicide rate in the United States, 5 per 100,000, or over 1,000 times that in Norway, about 0.5 per 100,000. Archaeological evidence from premodern societies is consistent with this level of violence.

We should pause to take in the significance of these numbers. With a death rate of over 500 per 100,000, or 0.5 percent, a typical inhabitant of this society has about a 25 percent likelihood of being killed within a period of fifty years—so a quarter of the people you know will be violently killed during their lifetimes. It is hard for us to imagine the unpredictability and fear that such brazen social violence would imply.

Though a lot of this death and carnage was due to warring between rival tribes or groups, it wasn’t just warfare and intergroup conflict that brought incessant violence. The Gebusi of New Guinea, for example, have even higher murder rates—almost 700 per 100,000 in the precontact period of the 1940s and 1950s—mostly taking place during peaceful, regular times (if times during which almost 1 in 100 of the population gets murdered each year can be called peaceful!). The reason appears to be related to the belief that every death is caused by witchcraft, which triggers a hunt for the parties responsible for even nonviolent deaths.

It’s not just murder that makes the lives of stateless societies precarious. Life expectancy at birth in stateless societies was very low, varying between twenty-one and thirty-seven years. Similarly short lifespans and violent deaths were not unusual for our progenitors before the past two hundred years. Thus many of our ancestors, just like the inhabitants of Lagos, lived in what the famous political philosopher Thomas Hobbes described in his book Leviathan as

continuall feare, and danger of violent death; And the life of man, solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short.

This was what Hobbes, writing during another nightmarish period, the English Civil War of the 1640s, described as a condition of “Warre,” or what Kaplan would have called “anarchy”—a situation of war of all against all, “of every man, against every man.”

Hobbes’s brilliant depiction of Warre made it clear why life under this condition would be worse than bleak. Hobbes started with some basic assumptions about human nature and argued that conflicts would be endemic in any human interaction. “If any two men desire the same thing, which nevertheless they cannot both enjoy, they become enemies; and … endeavor to destroy, or subdue one an other.” A world without a way to resolve these conflicts was not going to be a happy one because

from hence it comes to passe, that where an Invader hath no more to fear, than an other mans single power; if one plant, sow, build, or possesse a convenient Seat, others may probably be expected to come prepared with forces united, to dispossess and deprive him, not only of the fruit of his labour, but also of his life, or liberty.

Remarkably, Hobbes anticipated Pettit’s argument on dominance, noting that just the threat of violence can be pernicious, even if you can avoid actual violence by staying home after dark, by restricting your movements and your interactions. Warre, according to Hobbes, “consisteth not in actuall fighting; but in the known disposition thereto, during all the time there is no assurance to the contrary.” So the prospect of Warre also had huge consequences for people’s lives. For example, “when taking a journey, he arms himself, and seeks to go well accompanied; when going to sleep, he locks his dores; when even in his house he locks his chests.” All of this was familiar to Wole Soyinka, who never moved anywhere in Lagos without a Glock pistol strapped to his side for protection.

Hobbes also recognized that humans desire some basic amenities and economic opportunities. He wrote, “The Passions that encline men to Peace, are Feare of Death; Desire of such things as are necessary to commodious living; and a Hope by their Industry to obtain them.” But these things would not come naturally in the state of Warre. Indeed, economic incentives would be destroyed.

In such condition there is no place for industry, because the fruit thereof is uncertain, and consequently no culture of the earth, no navigation nor use of the commodities that may be imported by sea, no commodious building, no

--">