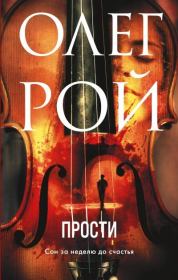

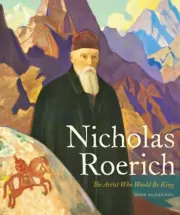

John McCannon - Nicholas Roerich: The Artist Who Would Be King

| Название: | Nicholas Roerich: The Artist Who Would Be King |

Автор: | John McCannon | |

Жанр: | Критика, История искусства | |

Изадано в серии: | неизвестно | |

Издательство: | неизвестно | |

Год издания: | 2022 | |

ISBN: | неизвестно | |

Отзывы: | Комментировать | |

Рейтинг: | ||

Поделись книгой с друзьями! Помощь сайту: донат на оплату сервера | ||

Краткое содержание книги "Nicholas Roerich: The Artist Who Would Be King"

Russian painter, explorer, and mystic Nicholas Roerich (1874–1947) ranks as one of the twentieth century’s great enigmas. Despite mystery and scandal, he left a deep, if understudied, cultural imprint on Russia, Europe, India, and America. As a painter and set designer Roerich was a key figure in Russian art. He became a major player in Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, and with Igor Stravinsky he cocreated The Rite of Spring, a landmark work in the emergence of artistic modernity. His art, his adventures, and his peace activism earned the friendship and admiration of such diverse luminaries as Albert Einstein, Eleanor Roosevelt, H. G. Wells, Jawaharlal Nehru, Raisa Gorbacheva, and H. P. Lovecraft. But the artist also had a darker side. Stravinsky once said of Roerich that “he ought to have been a mystic or a spy.” He was certainly the former and close enough to the latter to blur any distinction. His travels to Asia, supposedly motivated by artistic interests and archaeological research, were in fact covert attempts to create a pan-Buddhist state encompassing Siberia, Mongolia, and Tibet. His activities in America touched Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s cabinet with scandal and, behind the scenes, affected the course of three US presidential elections. In his lifetime, Roerich baffled foreign affairs ministries and intelligence services in half a dozen countries. He persuaded thousands that he was a humanitarian and divinely inspired thinker—but convinced just as many that he was a fraud or a madman. His story reads like an epic work of fiction and is all the more remarkable for being true. John McCannon’s engaging and scrupulously researched narrative moves beyond traditional perceptions of Roerich as a saint or a villain to show that he was, in many ways, both in equal measure.

Читаем онлайн "Nicholas Roerich: The Artist Who Would Be King". [Страница - 3]

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- . . .

- последняя (250) »

Before setting out, Roerich had told the world that his journey's aims were artistic and academic. He wished to paint the Himalayas and other remote parts of Asia. An amateur archaeologist and ethnographer, he hoped to study the myths and folklore of this poorly understood corner of the earth. He completed his canvases and conducted his research, but kept his primary goal a secret from the press and the public: Roerich went to the east desiring to locate the legendary kingdom of Shambhala and, using it as a foundation, establish a pan-Buddhist state of his own, encompassing Mongolia, Central Asia, the Himalayas, and parts of Siberia. Fulfilling this "Great Plan," he believed, would give a final turn to the cosmic wheel. Maitreya, the Buddha of the Future, would manifest himself and shepherd the world through apocalypse to an age of peace and beauty.

Roerich's expedition, of course, ushered in no such epoch. He failed even to reach Lhasa, and his party was expelled from Tibet after a brutal—and, for some, fatal—winter in the highlands. This did not stop him from claiming fame on the order of explorers like Sven Hedin, Aurel Stein, and Roy Chapman Andrews. Seven years later, he received another chance to bring his Great Plan to fruition, during a trip sponsored by one of Franklin Roosevelt's cabinet members and paid for by the US government. This second venture faltered as badly as the first, precipitating scandals that influenced the outcome of no fewer than three presidential elections.

In his seventy-three-year lifetime, Ro- erich came to know the world's most famous artists, celebrities, and political leaders. He baffled foreign-affairs and intelligence services in half a dozen countries. Thousands saw in him a profound, if not divinely inspired, humanitarian, while others thought him a fraud or a madman. One of his colleagues, the art historian Igor Grabar, remarked with bemusement that "about Roerich, one could write a most fascinating novel."1 Indeed, his tale is worthy of the pen of a Jules Verne or a Rudyard Kipling, whose Himalayan-adventuring antiheroes in The Man Who Would Be King are matched by the artist for sheer audacity. It is all the more remarkable for being true.

••

Roerich is a household name in his native Russia, and he has a reputation in India, where he lived for more than twenty years. Those who have heard of him in Europe and North America tend to know one or two aspects of what was an extraordinarily complicated life. He is familiar to specialists in Russian art and to aficionados of ballet and opera, and scholars of American history still study his impact on FDR-era politics. Fans of his visually distinctive art continue to grow in number, in the West as well as in Russia, and his following among "new age" devotees is correspondingly large. His fame is not meager, but better thought of as oddly compartmentalized.

Even a partial list of Roerich's accomplishments should make all but the most incurious wish to hear more about him. He designed for Diaghilev's Ballets Russes and, with Igor Stravinsky, cowrote the libretto for The Rite of Spring; his sets and costumes were onstage when the ballet made its immortal premiere in 1913. Before the communist takeover of 1917, Roerich became Russia's most renowned painter of scenes from Slavic antiquity, and he rose to direct one of the country's largest art schools; among those studying under him was a young Marc Chagall. After the revolution, Roerich and his family emigrated to England, where he befriended H. G. Wells and modern India's greatest poet, Rabindranath Tagore. He then went to America, making his mark as an artist, explorer, and peace activist. To house his art and his many enterprises, his supporters erected a landmark skyscraper that still towers over Manhattan's Riverside Drive. The 1925-1928 expedition added not just to his own stature, but to the larger Tibetomania that inspired James Hilton to create the Himalayan dreamland of Shangri-La in his 1933 bestseller, Lost Horizon. Roerich's efforts on behalf of a treaty to protect art and architecture in times of war—the so-called Roerich Pact, signed into law by the United States and twenty-one other nations in 1935—earned him praise from George Bernard Shaw, Albert Einstein, and Eleanor Roosevelt, and multiple nominations for the Nobel Peace Prize. In the 1930s, Roerich and his circle entered into a relationship with the US secretary of agriculture and future vice president, Henry A. Wallace, and, for a time, had the ear of President Roosevelt himself. In his old age, residing in the Punjab, the artist became a favorite of Jawaharlal Nehru, India's first prime minister, and it was Nehru who delivered the eulogy when Roerich died in 1947.

In various and sometimes curious ways, Roerich's influence has persisted and grown. Every American encounters him on a daily basis without knowing it: the inclusion of the Great Seal's Eye of Providence on the one-dollar bill, part of the currency redesign carried out in 1935 by treasury secretary Henry Morgenthau, was suggested by Henry Wallace, with approval and encouragement from Roerich. The cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, the first human being to gaze upon the earth from space, likened this unprecedented experience to his first encounter with Roerich's paintings.2 In 1974, on the centenary of Roerich's birth, India's prime minister Indira Gandhi dubbed him a "combination of modern savant and ancient rishi" Between 1987 and 1991, the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev established the grand museum complex in downtown Moscow that, until 2017, was administered by the International Center of the Roerichs. The Hague convention governing the treatment of cultural property during times of armed conflict is modeled in large part on Roerich's 1935 pact.4 In recent years, his paintings have fetched steadily higher prices at auction houses like Sotheby's and Christie's, and they form part of many key collections of Russian art.s

•

But to all this, there is a shadow y underside. Stravinsky once said of Roerich that "he looked as though he ought to have been a mystic or a spy."6 And while the composer had his own reasons for casting his onetime friend in such suspicious light, Roerich was self-avowedly the former and, if not literally the latter, close enough to make the distinction semantic.

No later than 1905, Roerich and his wife Helena took up a variety of esoteric doctrines and practices, among them The- osophy. By itself, this was nothing strange: the Victorian-era crisis of faith caused Europeans in huge numbers to embrace alternative spiritualities as a way of "searching for a soul," to borrow Carl Jung's phrase, in an increasingly secular world.7 Public figures drawn to such beliefs, whether temporarily or permanently, include Arthur Conan Doyle, the French actress Sarah Bernhardt, the inventors Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla, the Dutch painter Piet Mondrian, and Frank Lloyd Wright. Russia was part of this trend, and so much in its forefront that, as the historian Maria Carlson has observed, studying late tsarist Russia without reference to the occult is like studying medieval Europe without reference to Roman Catholicism.8 In such an environment, it would have seemed almost more odd not to experiment with mysticism. Even so, by the early 1910s, the Roerichs

--">- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- . . .

- последняя (250) »

Книги схожие с «Nicholas Roerich: The Artist Who Would Be King» по жанру, серии, автору или названию:

|

| Oleg Kleonov - Steal Like artist Communist Жанр: Изобразительное искусство, фотография Год издания: 2020 |

|

| Валентин Петрович Катаев, Марк Соломонович Гроссман, Борис Сенкевич и др. - Каменный пояс, 1979 Жанр: Советская проза Год издания: 1979 |