Nancy Kollmann - The Russian Empire 1450-1801

Название: | The Russian Empire 1450-1801 | |

Автор: | Nancy Kollmann | |

Жанр: | История: прочее | |

Изадано в серии: | неизвестно | |

Издательство: | неизвестно | |

Год издания: | 2017 | |

ISBN: | неизвестно | |

Отзывы: | Комментировать | |

Рейтинг: | ||

Поделись книгой с друзьями! Помощь сайту: донат на оплату сервера | ||

Краткое содержание книги "The Russian Empire 1450-1801"

Новая книга профессора Стэнфордского университета Нэнси Шилдс Коллманн представляет собой смелую попытку охватить в одном томе несколько веков российской истории – от возникновения Московского государства в середине XV столетия до смерти Павла I в 1801 г. Вопреки давней историографической традиции автор не противопоставляет друг другу "московский" и "петербургский" периоды, а рассматривает их как последовательные фазы развития империи раннего Нового времени (an early modern empire).

Читаем онлайн "The Russian Empire 1450-1801". [Страница - 3]

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- . . .

- последняя (201) »

Finding an organizational framework for such a large project, spanning more than three centuries and thousands of square miles, is tricky, since one runs the risk of reifying a constantly changing historical reality or imposing modern categories on the past. Russian history has certainly seen plenty of that—early modern Russia since the sixteenth century has been labeled a despotism and its people uncivilized, primarily in comparison to Europe. Not only normative, this trope is either teleological, suggesting a European path of development on which Russia is, at best, lagging, if not entirely left out, or essentialist, suggesting that Russians can never assimilate western values. Happily, recent scholarship has provided the foundations for thinking more complexly about early modern Russia as state and society. Since the 1970s scholars (primarily in America) have been exploring "how autocracy worked," overturning images of a literally all-powerful tsar in favor of a politics where the great men of the realm and their clans upon whom governance relied were consulted and engaged in decision making; new work has seen implicit limitation on the autocratic power of the ruler in Russia's religiously based ideology and in the realities of geography, distance, and sparse demography. Furthermore, research on the Russian empire was energized by the collapse of the Soviet Union, producing valuable studies of the constituent communities of the empire by scholars in Europe, America, and post-Soviet republics. Some of the useful tacks in new work on the Russian empire include resisting a teleology that assumes that empire moves into nation, resisting normative disapproval of empire, and placing the Russian empire in its Eurasian context. Without at all suggesting that a more complex "consensus-based" politics diluted the tsar's undivided sovereignty, this research forces us to look pragmatically at the forces through which the autocratic center governed the realm.

Particularly influential for this study is the model of an "empire of difference," developed by scholars including the Russianist Jane Burbank, the Africanist Frederick Cooper, and the Ottomanist Karen Barkey. Such empires rule from the center but allow the diverse languages, ethnicities, and religions of their subject peoples to remain in place as anchors of social stability. Such an analytical framework is not new, of course. In 1532 none other than Niccolo Machiavelli outlined three choices available to a conquering state to govern states that "have been accustomed to live in freedom under their own laws." Conquerors could "destroy" the vanquished; they could "go and live therein" by sending in administrators trained from the center; or they could "allow them to continue to live under their own laws, taking a tribute from them and creating within them a new government of a few which will keep the state friendly to you."

The Russian, Ottoman, Safavid, Mughal, and Chinese empires, all of which arose in the wake of the Mongol empire, demonstrate such an approach. Vast, continental, and highly diverse in ethnicities, confessions, and languages, these Eurasian empires calculated central control against the advantages of maintaining stable communities. They synthetically drew on the Chinggisid heritage of the Mongol empire (founded by Chinggis or Genghis Khan) and other cultural influences (in Russia, Byzantium; in the Ottoman empire, Byzantium and Islamic thought; in China, Confucianism and Buddhism; in Mughal India, indigenous Hindu practice) to construct ruling ideologies and governing strategies. Thomas Allsen reminds us that such an early modern empire was a "huge catchment basin channeling, accumulating, and storing the innovations of diverse peoples and cultures," while Alfred Rieber identifies common strategies of governance and ideology across "Eurasian borderlands" from Hungary to China. Connected by trade, warfare, and conquest, early modern empires shared military technologies, bureaucratic record-keeping skills, languages, communications networks, and ideologies and approaches to governance through "difference."

The Russian empire evolved in a part of Eurasia that acquainted it with multiple examples of politics of difference and empire. The territory that the Russian empire came to occupy traversed a geological and historical triad of east-west swaths of lands and cultures connecting Europe and Asia and north to south. Southernmost, stretching from the Mediterranean and Black Sea to the Middle East and points east, was a band of relatively commercialized societies, with large and densely populated cities and thick trade networks. Their needs—for food, luxury goods, and particularly for slave labor—were met by age-old maritime and overland trade routes, most notably the Silk Road that traversed the steppe as an east-west highway (with north-south offshoots) transferring people, goods, and ideas. Steppe prairieland constituted the middle of these three swaths of territory, north of the "civilized" urban world and linking it to the third swath, northern forests full of valuable resources such as slaves and furs. Riverine routes north-south linked forest, steppe, and urban emporia as long ago as Homer's time, when amber from the Baltic Sea made its way to the Mediterranean and Black Sea.

The lands that Russia came to control enter the picture among the Eurasian empires with the construction of trade networks from the Baltic to the Black and Caspian Seas in the ninth century, resulting in the emergence of a grand principality that called itself "Rus'," centered at Kyiv. It rose politically into the eleventh century on the great Dnieper River trade route to Byzantium and, in a fashion typical for medieval states, dissolved into multiple principalities in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries as trade routes shifted. Those principalities heir to Kyiv gravitated to trade opportunities in the west, the Baltic coast, and the upper Volga, which is where the princes of Moscow rose as a regional power in the fifteenth century. To some extent the Russian empire's rise marks a new stage in Eurasian empire building. Historically, empires had flourished in the Mediterranean, Middle East, Eurasia, and Far East, but they were difficult to maintain over time. Rome, the Mongols, and various Chinese dynasties historically were great successes in expanse and longevity, while more typical ofEurasia, particularly in the steppe, were constantly changing coalitions asserting control in segments of steppe or in smaller regions. From the fifteenth century onward, large continental empires became able to establish more enduring power and to control the steppe, because of improvements in communications, bureaucracy, and military. From the fifteenth to eighteenth century settled agrarian empires gradually took over the steppe—the Ottoman, Habsburg, Safavid, Mughal, Russian, and Qing empires—and Russia's role in that historical turning point is our story here.

Assertive central control established empire; what kept it together were flexible policies of governance, policies that ran along a continuum from coercion to co-optation to ideology, with a large middle embracing many forms of mobilization by rulers and accommodation by subjects. Charles Tilly calls this triad "coercion, capital and commitment." The various pieces of this continuum, which will provide a structuring principle for our work, had to be kept in balance. Coercion was essential and

--">- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- . . .

- последняя (201) »

Книги схожие с «The Russian Empire 1450-1801» по жанру, серии, автору или названию:

|

| Сергей Эдуардович Цветков - Узники Тауэра Жанр: История: прочее Год издания: 2001 |

|

| Александр Александрович Иессен - Греческая колонизация Северного Причерноморья Жанр: История: прочее Год издания: 1947 |

|

| Людмила Евгеньевна Морозова - Знаменитые женщины Московской Руси. XV—XVI века Жанр: История: прочее Год издания: 2014 |

|

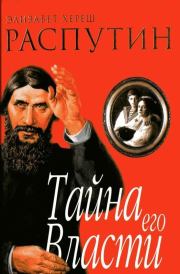

| Элизабет Хереш - Распутин. Тайна его власти Жанр: История: прочее Год издания: 2006 |